Finally, a collection of stories and poems of GB is

available in English.

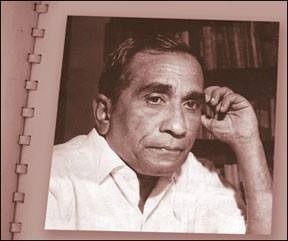

G.B. Senanayake (b. 1913) is a legendary Sinhala writer, who

made a remarkable contribution to the development of Sinhala fiction and poetry

during the mid-decades of the twentieth century. Vivette Ginige Silva has

translated this collection into English and published a single volume (Tharanga

Publisher 2020). Though Senanayake was an influential literary writer, a

critic, and an essayist comparable with early literary giants such as Martin

Wickramasinghe and Ediriveera Sarachchandra, this is the first time his work

has been translated into English. Vivette must be commended for taking up a

task that has been overlooked by many, including university scholars.

GB was a quintessential literary man committed to his art.

He was self-taught. In his numerous autobiographical essays, he has described

how he dedicated himself to learning literature. In early twentieth century,

when books were hard to come by, he used to regularly visit the Colombo public

library and to copy required books in his own handwriting. It is something that

might sound ridiculously old fashioned to some of us, whose Smart Phones

contain scanners and cameras.

His early essays

on world literature often refers to Western classics and modern masterpieces.

Many of them, he says, he has read from the Colombo public library. It is clear

from his essays that he read those classics from cover to cover because he

presents us with pleasingly clear summaries of those books. For example, in his

early essays on the Western classics, he neatly describes the plot summaries of

those huge books such as Odyssey. Those are not technical summaries; but

representations of the classics with his own original insights. What he learned

from by dedicated reading eventually enriched Sinhala literary culture for

decades. And he developed an appealingly lucid style for his Sinhala essays.

While he was at grade seven at Ananda College, he had to end

his formal education because of financial difficulties faced by his parents. He

gave up schooling but not learning. The Colombo Public Library became his

school and the university. By the time he turned to creative writing in his fifties,

he was considerably learned in nearly everything about literature. His

knowledge in English, not an unusual thing who attended a major school in the

country those days, helped him greatly. He continued to write to newspapers

until he caught the attention of none other than Martin Wickramasinghe, the

editor of Dinamina. Wickramasinghe offered GB a job at the national

daily. While working as a journalist GB continued to write books that belong to

many genres becoming one of the most prolific writers.

In his late sixties, he became blind. Perhaps, it was the endless

reading that destroyed his eyes. Even after he became fully blind, he wrote

more than a dozen of books, some of which was published posthumously. During

those later years, he dictated those novels to some relatives of him who copied

them down for him, eventually for us. He often liked to introduce himself as a psychological

writer who investigated complexities of the inner workings of human mind. It is

surely a thematic line that runs through his fictional work.

Now VGS has translated GB into English- Seven stories and

three poems. Though the slim volume is an admirable initial introduction of the

great literary man to the English audience, I wish there was an introductory

essay sketching out the significance of GB's contribution. His early stories,

some of which is translated in this book, demonstrate the influence of Edgar

Alan Poe, Guy de Maupassant, and Anton Chekov. Poe's influence was the most

pronounced in his famous stories which has a certain grotesque quality. In

fact, GB is the only major writer in Sinhala in terms of being influenced by

the art of the American writer. His famous stories such as "The Human

Heart" and "The Treasure Hidden" contain the grotesqueness found

in Edgar Alan Poe. Of course, Poe was a greater writer. "The Treasure

Hidden" was turned into a cinematic masterpiece by Lester James Pieris.

Without the brilliant script by Tissa Abesekara, however, GB's original story

alone could have led to that unparallel cinematic classic.

The

Craft of Fiction

Critics agree that

GB Senanayake was one of the first writers to pay serious attention to the

craft of fiction. He knew that the genre of short story was a unique art that

required meticulous craftsmanship. In his early books, Duppathuna Nethi

Lokaya (1945), Paligenima (1946) he paid careful attention to the

techniques of telling a story. By now Sinhala short story has developed so much

in its technique, the styles and the modes of representation. Without the early

experiments of writers such as GB, we would not have achieved such a growth in

fiction writing in Sinhala.

In "The

Treasure Hidden", we find a man who is looking for an ideal bride for him:

"Endless

was the effort I made to find her. For several months I visited the theaters in

Colombo. These visits were not

watch dramas but merely to trace her. Having visited the theaters, I stood at the point where the tickets were

being issued and carefully examined the faces of young damsels who streamed in. I am not such a hard-hearted person incapable

of deriving joy out of admiring the

beauty of women. But I looked at them bereft of the idea of admiring their elegance and grace. I only wanted to

see whether the spots to identify her were visible at least on the face of one these

women."

Translator has beautifully rendered the famous opening of

the most famous GB story. A man looks for certain 'spots' on his face of his

future bride, as we learn, when the story ends, to kill her at the 'door' of a

forest cave, in which ' a treasure' is believed to have been hidden. To get it,

a beautiful young woman with certain marks of beauty and 'luck' has be

sacrificed. Perhaps, in a hardcore feminist sense any traditional marriage is a

cave where women are sacrificed to get treasure (or pleasure) for men. Tissa

Abesekara, a writer with much wider vision than GB's, gave this story a

different meaning situating it in a colonial/postcolonial setting. That was in

his masterly filmscript of Nidhanaya. In the movie, Willie Abenayake a man who

outwardly shows that he has all the refinements brought about by colonial

education and 'civilization' but still believes in ancient treasures that can

be retrieved by human sacrificed.

(Nidhanaya)

poems in prose

GB's prose-poems, in

his 1946 book, Paligenima, are considered to be the precursor to Sinhala

Free Verse. Free verse-proper was to be written in early 1950s by Siri

Gunasinghe. But in 1946, GB indicated that poems can be written without

conventional rhymes and meters. Vivette, in this collection, has included the

translations of such poems. She could have included those originals too, one

feels, so that the reader could see what 'free verse' looked like in Sinhala

before it became so popular after 1950s.

Everything in this collection

has been translated with care and sensitivity required in translating the work

of a masterly writer like GB.

No comments:

Post a Comment